Two Centuries of Global Factor Premiums

Related to all major factor strategies (trend, momentum, value, carry, seasonality and low beta/volatility):

Authors: Baltussen, Swinkels, van Vliet

Title: Global Factor Premiums

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3325720

Abstract:

We examine 24 global factor premiums across the main asset classes via replication and new-sample evidence spanning more than 200 years of data. Replication yields ambiguous evidence within a unified testing framework with methods that account for p-hacking. The new-sample evidence reveals that the large majority of global factors are strongly present under conservative p-hacking perspectives, with limited out-of-sample decay of the premiums. Further, utilizing our deep sample, we find global factor premiums to be not driven by market, downside, or macroeconomic risks. These results reveal strong global factor premiums that present a challenge to asset pricing theories.

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

"In this paper we study global factors premiums over a long and wide sample spanning the recent 217 years across equity index (but not single securities), bond, currency, and commodity markets.

The first objective of this study is to robustly and rigorously examine these global factor premiums from the perspective of ‘p-hacking’.

We take as our starting point the main global return factors published in the Journal of Finance and the Journal of Financial Economics during the period 2012-2018: time-series momentum (henceforth ‘trend’), cross-sectional momentum (henceforth ‘momentum’), value, carry, return seasonality and betting-against-beta (henceforth ‘BAB’). We examine these global factors in four major asset classes: equity indices, government bonds, commodities and currencies, hence resulting in a total of 24 global return factors.4

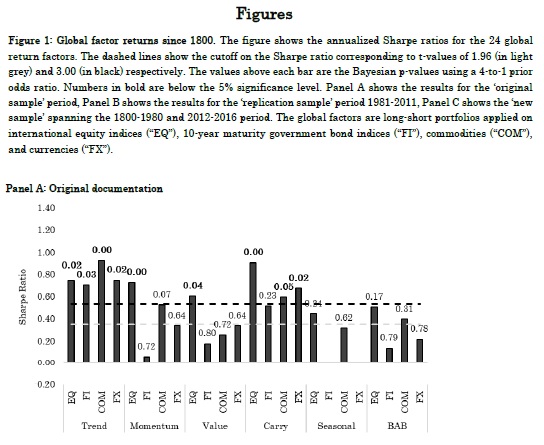

We work from the idea that these published factor premiums could be influenced by p-hacking and that an extended sample period is useful for falsification or verification tests. Figure 1, Panel A summarizes the main results of these studies.

Shown are the reported Sharpe ratio’s in previous publications, as well as the 5% significance cutoff in the grey-colored dashed line. In general, the studies show evidence on the global factor premiums, with 14 of the 22 factors (return seasonality is not tested in bonds and currencies) displaying significant Sharpe ratio’s at the conventional 5% significance level.

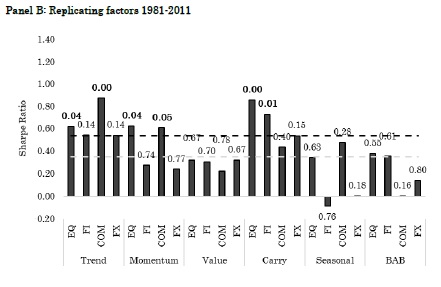

Further, most of the studies have differences in, amongst others, testing methodologies, investment universes and sample periods, choices that introduce degrees of freedom to the researcher. To mitigate the impact of such degrees of freedom, we reexamine the global return factors using uniform choices on testing methodology and investment universe over their average sample period (1981-2011). Figure 1, Panel B shows the results of this replicating exercise. We find that Sharpe ratios are marginally lower, with 12 of the 24 factor premiums being significant at the conventional 5% level.

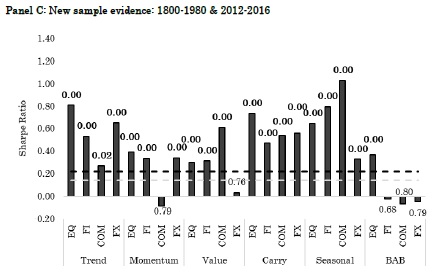

The second objective of this study is to provide rigorous new sample evidence on the global return factors. To this end, we construct a deep, largely uncovered historical global database on the global return factors in the four major asset classes. This data consists of pre-sample data spanning the period 1800- 1980, supplemented with post-sample data from 2012-2016, such that we have an extensive new sample to conduct further analyses. If the global return factors were unintentionally the result of p-hacking, we would expect them to disappear for this new sample period.

Our new sample findings reveal consistent and ubiquitous evidence for the large majority of global return factors. Figure 1, Panel C summarizes our main findings by depicting the historical Sharpe ratio’s in the new sample period. In terms of economic significance, the Sharpe ratios are substantial, with an average of 0.41. Remarkably, in contrast to most out-of-sample studies we see very limited ‘out-of-sample’ decay of factor premiums.

In terms of statistical significance and p-hacking perspectives, 19 of the 24 t-values are above 3.0,19 Bayesian p-values are below 5%, and the break-even prior odds generally need to be above 9,999 to have less than 5% probability that the null hypothesis is true."

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Check http://quantpedia.com/Screener

Do you want to see performance of trading systems we described? Check http://quantpedia.com/Chart/Performance

Do you want to know more about us? Check http://quantpedia.com/Home/About

Follow us on:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/quantpedia/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/quantpedia