Two Versions of CAPM

This week's analysis of selected financial research paper contains more text and no picture, but we still think it's worth reading …

Authors: Siddiqi

Title: CAPM: A Tale of Two Versions

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3350280

Abstract:

Given that categorization is the core of cognition, we argue that investors do not view firms in isolation. Rather, they view them within a framework of categories that represent prior knowledge. This involves sorting a given firm into a category and using categorization-induced inferences to form earnings and discount-rate expectations. If earnings-aspect is categorization-relevant, then earnings estimates are refined, whereas discount-rates are confounded with the category-exemplar. The opposite happens when discount-rates are categorization relevant. Earnings-focused approach such as DCF, generally used by institutional investors, leads to a version of CAPM in which the relationship between average excess return and stock beta is flat (possibly negative). Value effect and size premium (controlling for quality) arise in this version. Discount-rate focused approach such as multiples or comparables valuation, typically used by individual investors, leads to a second version in which the relationship is strongly positive with growth stocks doing better. The two-version CAPM accounts for several recent empirical findings including fundamentally different intraday vs overnight behavior, as well as behavior on macroeconomic announcement days. Momentum is expected to be an overnight phenomenon, which is consistent with empirical findings. We argue that, perhaps, our best shot at observing classical CAPM in its full glory is a laboratory experiment with subjects who have difficulty categorizing (such as in autism spectrum disorders).

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

"Consider the following two empirical observations:

Firstly, stock prices behave very differently with respect to their sensitivity to market risk (beta) at specific times. Typically, average excess return and beta relationship is flatter than expected. It could even be negative. However, during specific times, this relationship is strongly positive, such as on days when macroeconomic announcements are made or during the night.

Secondly, a hue, which is halfway between yellow and orange, is seen as yellow on a banana and orange on a carrot. In this article, we argue that the two observations are driven by the same underlying mechanism.

The second observation is an example of the implications of categorization for color calibration. In this article, we argue that the first observation is also due to categorization, which gives rise to two versions of CAPM. In one version, the relationship between expected return and stock beta is flatter than expected or could even be negative, whereas in the second version, this relationship is strongly positive.

Categorization is the mental operation by which brain classifies objects and events. We do not experience the world as a series of unique events. Rather, we make sense of our experiences within a framework of categories that represent prior knowledge. That is, new information is only understood in the context of prior knowledge.

Here, in accord with cognitive science literature, we present a view of categorization that has both an upside as well as a downside, and apply this nuanced perspective to the capital asset pricing model (CAPM). If categorization is fundamental to how our brains make sense of information, then investor behavior, like any other domain of human behaviour, should also be viewed through this lens. This means that the traditional view that each firm is viewed in isolation needs to be altered. When an investor considers a firm, she views it within a framework of categories that represent prior knowledge. This involves sorting a given firm into a category based on attributes that are deemed categorization-relevant. Categorization-induced inferences help refine such attributes while confounding categorization-irrelevant attributes with the category-exemplar.

Valuation requires estimating earnings (cash-flows) potential and estimating discount-rates. Even among firms that sell similar products (same sector) some may have more similar earnings potential, whereas other may have more similar discount-rates. The former type may include firms with similar earnings-related fundamentals but very different levels of debt ratio and equity betas. Also, their multiples (generally related to inverse of the discount-rate) such as P/E, EV/Sales or EV/EBITDA could be very different. The latter type may include firms with similar debt ratios and equity betas or similar P/E and EV/EBITDA but quite different earnings or cash-flows fundamentals.

We argue that, an earnings-focused approach, such as discounted cash-flows (DCF), tends to categorize the former type of firms together, whereas, the relative valuation approach (RV) based on multiples such as P/E or EV/EBITDA tends to categorize the latter types of firms together. In other words, the choice of a valuation approach introduces a bias in how firms are categorized.

In this paper, we take discounted cash-flows (DCF) as the prototype of an earnings-potential focused approach, and valuation by multiples or relative valuation (RV) as the prototype discount-rate focused approach.

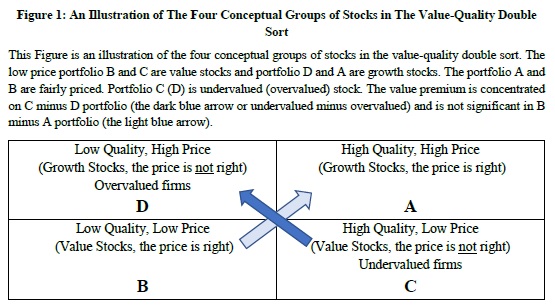

We show that when earnings aspect is categorization-relevant (as in DCF analysis), a version of CAPM is obtained, which displays a flatter or even negative relationship between stock beta and expected excess returns. Betting-against-beta anomaly is observed along with the value effect, as well as the size premium after controlling for quality (consistent with the findings in Asness et al 2018). We argue that this is the default version which typically prevails. While categorizing firms, if investors are focused on the discount rate aspect (as in RV analysis), then the discount-rates are refined whereas earnings estimates are confounded with the category-exemplar. A second version of CAPM arises. In this version, there is a strong positive relationship between beta and expected excess return.

One way to make sense of the co-existence of two versions is to classify investors as either earnings-focused or discount rate-focused. If earnings-focused investors dominate, then the first version is observed. If the discount-rate-focused investors dominate, then the second version is observed. Note, that earnings-focused approach (such as DCF) is typically employed by large institutional investors, whereas RV approach is associated with individual investors (and with sell-side equity analysts who publish research reports for individual investors).

If institutional investors are earnings-focused and individual investors are discount rate-focused, then the trading behavior of each type can be observed to make specific predictions:

1) Institutional investors typically avoid trading at the open and prefer to trade in the afternoon near the market close. The objective is to time the trade when the market is most liquid to avoid any adverse price impact. This means that trade at open is dominated by individual investors. So, one expects to see the relationship between stock beta and average return to be strongly positive (second version) overnight and flat or even negative (first version) intraday.

2) Institutional traders typically trade in the right direction prior to macroeconomic announcement days (suggesting superior information) with institutional trading volume falling sharply on macro-announcement days. As trade on such days is dominated by individual investors, one expects to see a strongly positive relationship (second version) on macro-announcement days.

3) The first version generally dominates intraday due to institutional investors being dominant. As the corresponding CAPM version comes with size and value effects, the prediction is that size and value are primarily intraday phenomena.

4) We show that, all else equal, discount rate-focused investors have higher willingness-to-pay than earnings-focused investors. If discount rate-focused investors dominate trade at open, whereas earnings-focused investors are active intraday, then one expects prices to typically rise overnight from close-to-open and fall intraday between open-to-close.

5) If momentum traders, who buy past winners and short past losers, are primarily individual investors, then one expects momentum to be an overnight phenomenon observed between close-to-open. This is because individual traders dominate trade at or near open.

"

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Check http://quantpedia.com/Screener

Do you want to see performance of trading systems we described? Check http://quantpedia.com/Chart/Performance

Do you want to know more about us? Check http://quantpedia.com/Home/About

Follow us on:

Facebook: https://www.facebook.com/quantpedia/

Twitter: https://twitter.com/quantpedia

Youtube: https://www.youtube.com/channel/UC_YubnldxzNjLkIkEoL-FXg

"

"