With financial markets increasingly whipsawed by geopolitical tensions and unpredictable policy shifts from the Trump administration—investors are once again questioning how to understand risk, fear, and the true drivers of returns. A recent and compelling paper dives into this debate with a provocative thesis: in “Fear, Not Risk, Explains Asset Pricing,” authors Rob Arnott and Edward McQuarrie argue that traditional models built on quantifiable risk have failed to explain real-world returns, and that fear—messy, emotional, and deeply human—is the missing piece.

The authors begin by challenging the foundational assumptions behind traditional risk-based models like the Capital Asset Pricing Model (CAPM) and the Efficient Market Hypothesis. They present a historical and empirical autopsy of the idea that taking on more risk necessarily leads to higher returns. Their analysis shows periods—some lasting decades—where equities failed to outperform supposedly “safer” government bonds, both in the U.S. and internationally. Far from being anomalies, these episodes are seen as repeated failures of risk theory to explain actual investor outcomes. Instead, Arnott and McQuarrie argue that human emotions—especially fear of loss (FoLI) and fear of missing out (FoMO)—offer a more compelling explanation for investor behavior and asset price movement over time.

They propose a new paradigm, one that is investor-centric rather than asset-centric, built not on tidy math but on behavioral truths. Under this framework, fear is multi-dimensional and dynamic, oscillating between panic and euphoria. It explains everything from meme stocks to market crashes, and even why investors pile into low-yield assets despite knowing the math doesn’t add up. This model—the so-called Deranged Asset Pricing Model (DAPM)—doesn’t discard traditional risk metrics, but it suggests that our models are “looking for keys under the lamppost” while the real drivers of returns hide in the emotional dark alley of investor psychology.

Authors: Robert D. Arnott and Edward F. McQuarrie

Title: Fear, Not Risk, Explains Asset Pricing

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5127501

Abstract:

Risk theory has dominated the asset pricing literature since the 1960s. We chronicle empirical failures of risk theory in its prediction of the excess return on equities, to lay the groundwork for a complementary framework, investor-focused rather than asset-focused, and centered on fear rather than objective measures of risk. A fear premium puts fear of missing out on a par with fear of loss. Most anomalies and factors of the past half-century would have been expected, given a fear-based model for returns. The new paradigm is offered as a starting point to advance investment science.

As always, we present several interesting figures and tables:

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

“The fear paradigm does not dispute that human investors are loss averse. FoLI, fear of losing it, motivates many human investment decisions. But the fear paradigm has a broader definition of loss. FoMO—loss of gain or opportunity cost—may be just as aversive as loss of principal, especially when a bull market fosters boundless optimism. A guaranteed return of only two basis points, when 30% returns may be available, is aversive. It can only be overcome by some greater aversion, as when a loan shark threatens. Again, human investors are afraid of many things. There can be no meaningful wealth accumulation at two basis points per year. For the human investor, it can be just as scary to never get anywhere as to lose some of what one already has.

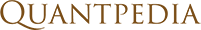

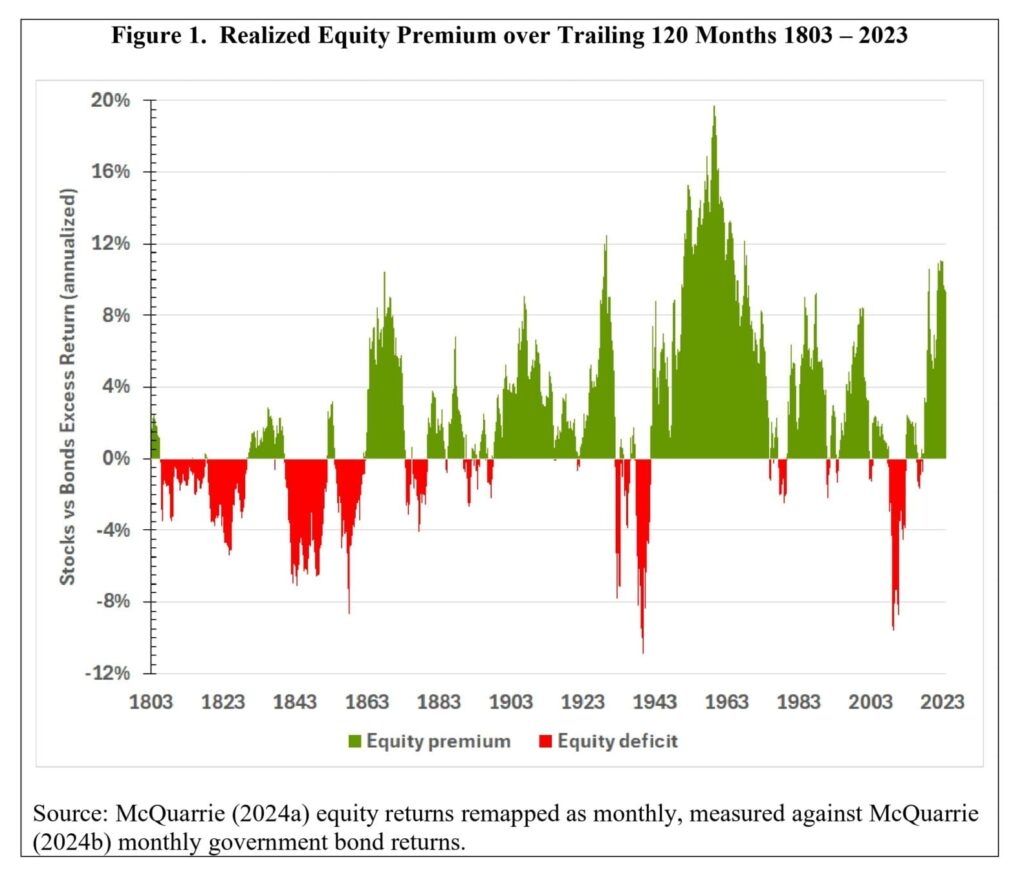

However, these initial results were subject to dispute, insofar as McQuarrie’s measure of bond returns prior to 1926 had sometimes included corporate bonds as well as government bonds. Given their additional idiosyncratic risks, inclusion of corporate bonds undercut the desired comparison of a more to less risky asset. More recently he addressed that objection by constructing a new measure of bond returns from 1793 that uses government bonds exclusively, and Treasury bonds whenever available (McQuarrie 2024b). Figure 1 plots the real equity premium or deficit over the rolling 10-year (120-month) spans from January 1793 to December 2023 using that new government bond index and the McQuarrie (2024a) stock returns. Equity deficits are observed again and again, in recent years as well as in the 19 th century. Figure 2 shows that investors sometimes had to wait until their great-grandchildren were fully grown before receiving a cumulative profit from exhibiting a preference for equities. It bears mention that these results are for the US, which has had among the best long-term real stock market returns in the world (Jorion and Goetzmann 1999).

These results are not compatible with the hypothesis that risk, as measured by standard deviation, provides an index of the rewards that investors demand to receive, i.e., that riskier assets are priced to deliver higher returns when held for a long period. Risk fails the test of precision; or more exactly, the precision of risk is a distraction, with its precise measurement not panning out as far as prediction is concerned.

Risk theory would seem to predict that pre-SEC stock market returns would have had to be higher, to account for the greater risk of stock investing before that protective legislation was put in place. Rephrasing the quote from Goetzmann and Ibbotson, the 19th century stock investor would have demanded a greater equity risk premium, to reflect the much greater dangers of stock investing in the decades before the new securities legislation. Likewise, post-1930s returns should be comparatively lower for stocks, given the substantial reduction in risk once the SEC was on the beat.

But history shows otherwise. Figure 5 splits the record at the end of 1935, and charts real returns over the prior 65 years to the beginning of the Cowles (1939) data, and forward 65 years to the end of 2000. Given the tumultuous events surrounding the legislation, Figure 5 grays out the five years on either side of that hinge date, and the quantitative analysis compares results from before 1931 with results after 1940.28

Historical data show too much mispricing of equity values for this derangement to have issued from rational decisions made collectively by risk-averse actors. Fear positively predicts mispricing, and the extent to which mispricing is visible and common, out in the world of investing, provides supporting evidence for the fear paradigm. More generally, derangement implies that markets will be difficult to predict using any objective factor such as risk. What investors fear at any given moment is subject to constant change. Sometimes there is a flight to safety. Sometimes there is fear of missing out. In that sense, DAPM is fully consistent with those versions of the Efficient Market Hypothesis which hold that future stock returns are difficult to predict.”

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Sign up for our newsletter or visit our Blog or Screener.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Premium service? Check how Quantpedia works, our mission and Premium pricing offer.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Pro service? Check its description, watch videos, review reporting capabilities and visit our pricing offer.

Are you looking for historical data or backtesting platforms? Check our list of Algo Trading Discounts.

Or follow us on:

Facebook Group, Facebook Page, Twitter, Linkedin, Medium or Youtube

Share onLinkedInTwitterFacebookRefer to a friend