The United States has a special place in a global financial system. The U.S. dollar is the world’s reserve currency, and U.S. Treasuries are used as primary safe assets. Therefore, it is no surprise that the U.S. has some benefits from this arrangement. Academic research paper written by Krishnamurthy & Lustig shows that the U.S. derives a “convenience yield” from a demand of foreign investors. They consequently incur lower returns on their holdings of dollar-denominated safe assets. The FED’s conventional and unconventional monetary policy actions directly impact the supply of dollar-denominated safe assets. These decisions also affect the size of convenience yield, which causes moves in global financial markets...

Authors: Krishnamurthy, Lustig

Title: Mind the Gap in Sovereign Debt Markets: The U.S. Treasury basis and the Dollar Risk Factor

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=3443231

Abstract:

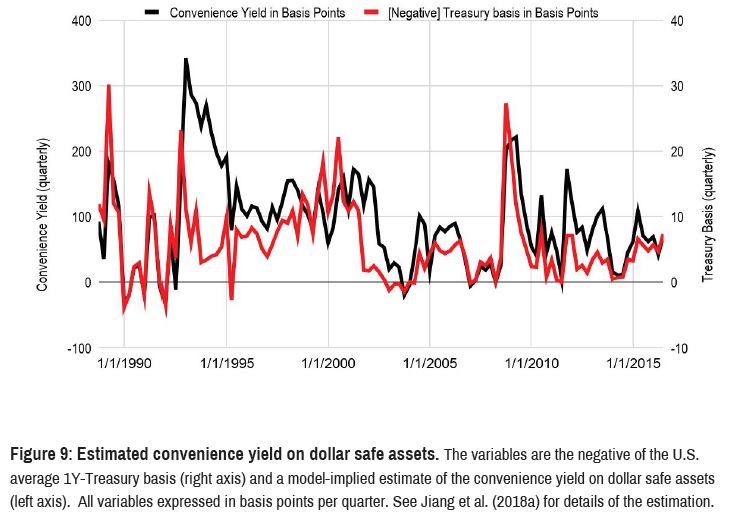

The U.S. dollar exchange rate clears the global market for dollar-denominated safe assets. We find that shifts in the demand and supply of safe dollar assets are important drivers of variation in the dollar exchange rate, bond yields, and other global financial variables. An increase in the convenience yield that foreign investors derive from holding safe dollar assets causes the dollar to appreciate, and incentivizes foreign debtors to tilt their issuance towards dollar-denominated instruments. U.S. monetary policy also affects the dollar exchange rate through its impact on the supply of safe dollar assets and the convenience yield. Interest rate spreads with foreign countries are not sufficient statistics to gauge the impact of the stance of U.S. monetary policy on currency markets. The U.S. Treasury basis, which measures the yield on an actual U.S. Treasury minus the yield on an equivalent synthetic U.S. Treasury constructed from a foreign bond, provides a direct measure of the global scarcity of dollar safe assets.

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

“When the U.S. issues dollar-denominated IOUs to foreign investors, the U.S. also exports the liquidity and safety services provided by its supply of dollar-denominated safe assets. Foreign investors derive a convenience yield, which reflects the value of these liquidity and safety services, on their holdings of dollar-denominated safe assets, lowering their required return. Thus, the key footprints of safe asset demand are the exceptionally low effective returns realized by foreign investors purchasing Treasurys whose timing suggests a reverse currency carry trade. The U.S. collects ‘seignorage’ from the rest of the world on its issuance of safe dollar assets.

The U.S. dollar exchange rate plays a key role in clearing the global market for dollar-denominated safe assets. When the marginal willingness of foreign investors to pay for dollar-denominated safe assets rises, the dollar appreciates to induce an expected depreciation and thus lower the returns expected by foreign investors on their holdings of dollar-denominated safe assets. We show that shifts in the demand and supply of safe dollar assets are important drivers of variation in the dollar exchange rate, bond yields, and other global financial variables. The global financial cycle is in part a dollar cycle.

The Federal Reserve’s conventional and unconventional monetary policy actions directly impact the global supply of dollar-denominated safe assets and the dollar exchange rate. When the Fed tightens, the bond markets infer that a reduction in the supply of safe dollar assets is imminent. As a result of this supply shift, the marginal willingness of global investors to pay for the safety and liquidity of dollar-denominated assets – as measured by the convenience yield on these assets – increases, leading to an appreciation of the dollar in response to this increase in the convenience yield (even when controlling for interest rates). We refer to this as the convenience yield channel of monetary policy, and we document strong empirical support for this channel.

Dollar liquidity is provided by safe dollar bonds that are issued not only by the U.S. government, but also by foreign governments, U.S. and foreign banks, as well as multinationals. The demand for dollar safe assets, and the convenience yield, drives funding and capital structure decisions inside and outside of the U.S. Outside of the U.S., debtors around the world, especially in emerging market countries, are short the dollar because they seek to benefit from the funding advantages of issuing dollar bonds. As a result, foreign borrowers, especially those not exporting and invoicing in dollars, may be subject to a currency mismatch. When the dollar exchange rate appreciates, e.g., because the Fed tightens and the supply of safe assets shrinks, the debt burden in local currency of these foreign borrowers increases. In countries that rely more heavily on dollar funding, we find that the local currency depreciates more against the U.S. dollar in response to an increase in the safe asset convenience yield, and the net effect of the convenience yield increases on the country’s external debt burden is larger.

The demand for safe dollar assets also affects the capital structure inside the U.S. The U.S. collects safe asset seignorage on its issuance of dollar bonds to foreign investors, as attested by the exceptionally low returns foreign investors earn on their net purchases of Treasurys. This has shaped the highly levered aggregate capital structure of the U.S. relative to the rest of the world. On the private side, the demand for safe dollar bonds incentivizes financial intermediaries to issue more `safe’ dollar bonds backed by risky collateral, thus increasing private leverage in the U.S. Whenever there is a crisis in global financial markets, the convenience yield on dollar safe assets increases persistently, strengthening the dollar’s funding advantage, and incentivizing foreign issuers to tilt future issuance even more towards the dollar, thus sowing the seeds for the next crisis. We refer to this dynamic as the dollar cycle.

We show that variation in the market’s assessment of current and future convenience yields, as measured by the Treasury basis, is a major driver of variation in the dollar exchange rate. Shocks to the demand and supply of dollar-denominated safe assets will alter the expected path of future convenience yields, the basis, and hence the dollar exchange rate. When the convenience yield increases and the U.S. basis widens, the dollar tends to appreciate against G-10 currencies. Since the financial crisis, as the dominance of the dollar has increased, this convenience yield effect on the dollar exchange rate has strengthened even further.

Interest rate spreads with foreign countries provide an incomplete picture to gauge the impact of the stance of U.S. monetary policy on currency markets. The Treasury basis, since it measures the convenience yield on dollar safe assets, completes the picture. We show that monetary policy directly impacts the convenience yields (basis) and hence exchange rates, because the stance of monetary policy is perceived by market participants to affect the supply of dollar safe assets. When the Fed tightens by raising the Fed Funds Rate target, the future supply of dollar denominated safe assets is expected to shrink, resulting in a widening of the U.S. Treasury basis and an appreciation of the dollar, even after controlling for interest rate changes. We use FOMC-induced variation in the US Treasury basis around FOMC announcements to help us identify the causal effect of variation in the basis on the dollar exchange rate.

While the average Treasury basis against other G-10 currencies is consistently negative, there is a substantial amount of cross-sectional variation amongst the G-10 in the bilateral U.S. Treasury bases against individual currencies. Local institutions (governments, financial intermediaries) may affect the bilateral bases. Convenience yields are not exclusively driven by safe asset demand. Investment currencies, i.e. currencies with high local interest rates (e.g., AUD and NZD), tend to see large positive bilateral Treasury bases, because local institutional investors want to go long in synthetic dollars, not cash dollars, to hedge their short dollar exposure. These countries typically see large net inflows of dollar investments. This force offsets the safe asset demand for cash dollars and renders the dollar basis positive. When the average Treasury basis widens, these investment countries see a much larger depreciation of their currency against the dollar: the convenience yield of dollar assets increases more in these investment countries than in funding currencies. As a result, whenever global investors around the world flock to the safety of dollar assets, these countries, which are net short the dollar, experience a larger depreciation of their currency.”

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Sign up for our newsletter or visit our Blog or Screener.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Premium service? Check how Quantpedia works, our mission and Premium pricing offer.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Pro service? Check its description, watch videos, review reporting capabilities and visit our pricing offer.

Are you looking for historical data or backtesting platforms? Check our list of Algo Trading Discounts.

Or follow us on:

Facebook Group, Facebook Page, Twitter, Linkedin, Medium or Youtube

Share onLinkedInTwitterFacebookRefer to a friend