What can we realistically expect from investing across different asset classes over the long run? That’s the kind of big-picture question the “Long-Run Asset Returns“ paper tackles—offering a sweeping look at how stocks, bonds, real estate, and commodities have performed over the past 200 years. The paper goes beyond just listing historical returns—it explains how reliable (or not) those numbers are by digging into the quirks and issues hidden in very old data. The authors look at what happens to returns when you include countries or time periods that usually get left out, and they show that the past isn’t always as rosy—or as repeatable—as it might seem if you only look at recent decades.

For anyone experimenting with Quantpedia’s Black-Litterman model (announced a few days ago), this paper is a useful anchor. It gives context for setting your baseline return assumptions and helps you build more thoughtful views. Instead of just guessing or using recent performance, you can lean on a much deeper historical perspective—seeing what returns looked like in different eras, how unusual the 20th century really was, and why today’s market environment might call for more cautious expectations.

What are the key findings?

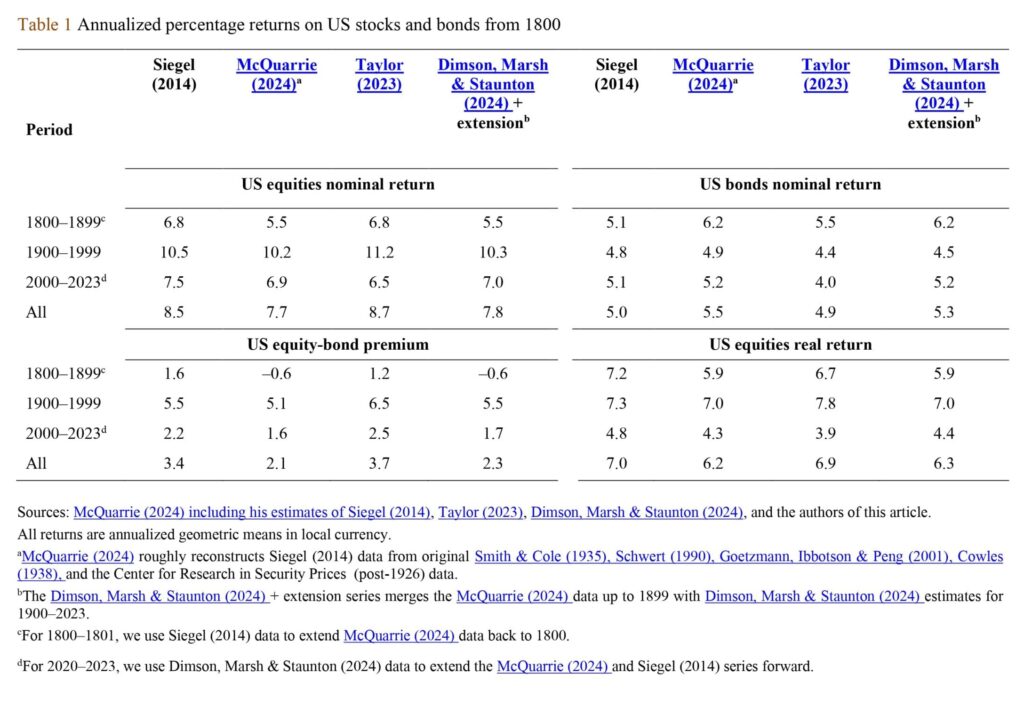

Equity Returns: The 20th-century equity premium (especially in the U.S.) was abnormally high, ranging from 4–6% over bonds. In contrast, 19th-century equity premia were close to zero or even negative in some datasets.

Bond Yields: Bond yields were historically much higher—even during times of low growth and inflation (pre-1900s)—and the ultra-low yields in the 2000s and 2010s were historically unprecedented.

Credit Premia: Long-run excess returns on corporate bonds over government bonds are small (about 0.75%–1%) and difficult to estimate reliably due to limited pre-1970s data.

Real Estate: While real estate is important for household wealth, long-run total returns (including rental income) appear lower than equities, especially after adjusting for costs and quality improvements.

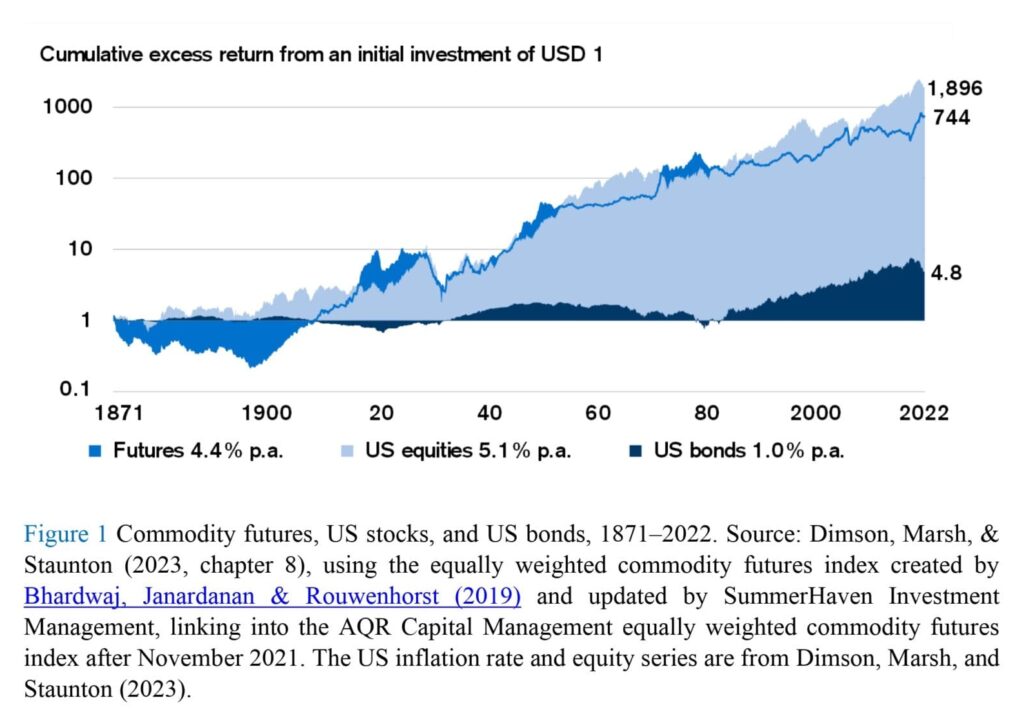

Commodities: While spot commodity investments have low or negative real returns, diversified portfolios of commodity futures have historically earned a 3–4% annual premium, largely due to diversification and rebalancing effects.

To provide a comprehensive understanding of long-run asset returns, we encourage readers to examine Figure 1, which illustrates that commodity futures have almost matched the long-run returns of US equities over a 152-year window and even exceeded equity investment returns since 1900. Additionally, Table 1 summarizes the annualized nominal returns of equities and bonds, the equity risk premium over bonds, and the annualized real returns of equities during 1800–1899, 1900–1999, and 2000–2023. Notably, the figures presented are geometric means (compound returns), typically lower than arithmetic means (simple returns), especially for more volatile series.

Authors: David Chambers, Elroy Dimson, Antti Ilmanen, Paul Rintamäki

Title: Long-Run Asset Returns

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=5022480

Abstract:

The literature on long-run asset returns has continued to grow steadily, particularly since the start of the new millennium. We survey this expanding body of evidence on historical return premia across the major asset classes-stocks, bonds, and real assets-over the very long run. In addition, we discuss the benefits and pitfalls of these long-run data sets and make suggestions on best practice in compiling and using such data. We report the magnitude of these risk premia over the current and previous two centuries, and we compare estimates from alternative data compilers. We conclude by proposing some promising directions for future research.

As continually, we present several interesting figures and tables:

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

“First, we address one of the central questions in empirical asset pricing, namely, whether stocks consistently beat bonds in the long run. Much of this evidence is based on studies of data series starting in 1900, or notably, 1926, in the case of US stocks and bonds—the start date of the CRSP (Center for Research in Security Prices) data set. The choice of start date matters. The evidence regarding average returns drawn from post-1900/1926 studies delivered the conventional wisdom that the long-run equity risk premium over bonds was substantially positive in the United States and in every other country with a long history. However, in returning to this question, we examine the pre-1900/1926 history of stock and bond returns—primarily in the United States and the United Kingdom. The evidence suggests that the gap between the average returns on stocks and on bonds was low in the United Kingdom and seemingly negligible in the United States.

Second, we examine just how abnormally low bond yields were in the two opening decades of the twenty-first century. When viewing the yields of government bonds (or other bonds with a low credit risk) in a much longer-run perspective, we conclude that recent yield experience was indeed unprecedented.

The third question concerns corporate bonds and the credit risk premium. The existing evidence on the extent of the excess returns or premia attributable to credit risk is based on a relatively short history stretching back to the 1970s. We therefore ask whether (or not) long-horizon corporate bond data histories can provide insights on credit excess returns. In brief, the evidence is at best mixed due to estimation problems and a paucity of data.

Our two remaining questions deal with real assets—real estate and commodities—and how compelling their long-run returns have been compared to equities. When reviewing the evidence on the investment performance of real estate, we discuss the challenges presented by the heterogeneity and immovability of this asset class. The evidence has largely focused on housing and suggests that total returns are below those from equities. We then turn to commodities and critically examine the claims of the recent studies pointing to surprisingly high long-run returns. Here, we conclude that the long-run historical returns on a diversified portfolio of futures have come close to approximating those on equities.

To sum up, the equity risk premium was exceptionally high in the twentieth century, while being low in the nineteenth century—notably in the United States. The reasons for these differences are worthy of further research. Both centuries may have been abnormal. Consistent with this, leading experts at a recent equity premium symposium estimated a prospective equity-bond premium of between 0% and 5% (Siegel & McCaffrey 2023, appendix A). The best guidance on future premia may be between the experience of the lucky 1900s and that of the disappointing 1800s.

This apparent puzzle of high real interest rates in a slow-growth world may be explained by capital scarcity, the impatience of savers at a time when most people lived near subsistence level, as well as high financial intermediation costs (Bernstein 2022). Most economists studying the fundamental determinants of real interest rates have focused on the expected consumption growth rate rather than time preference. While this is appropriate in the modern world, it seems less so in preindustrial times. Rogoff, Rossi & Schmelzing (2024) explored the Schmelzing data for structural breaks but find none after the Industrial Revolution; instead, real yields are trend stationary. Like us, the authors highlight opposing trends in real yields and real growth across centuries.12

Our final word on real estate is an appeal for more long-run empirical studies of total returns to housing using the best available data and avoiding the measurement problems highlighted above. It is also worth emphasizing that little has been done on the long-run performance of commercial real estate, farmland, and infrastructure.21 This is particularly important given their greater relevance to institutional investor portfolios than housing.

Summarizing, the historical evidence suggests that while single commodities may not be expected to outperform cash in compound returns, a diversified commodity futures portfolio can offer an expected premium of 3–4% per annum. Furthermore, it has achieved this over long periods—whether the past 150, 100, or 50 years. Overall, we conclude that this diversification return is the most important and empirically robust contributor to the positive long-term commodity premium.25”

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Sign up for our newsletter or visit our Blog or Screener.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Premium service? Check how Quantpedia works, our mission and Premium pricing offer.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Pro service? Check its description, watch videos, review reporting capabilities and visit our pricing offer.

Are you looking for historical data or backtesting platforms? Check our list of Algo Trading Discounts.

Or follow us on:

Facebook Group, Facebook Page, Twitter, Linkedin, Medium or Youtube

Share onLinkedInTwitterFacebookRefer to a friend