How to Construct a Long-Only Multifactor Credit Portfolio?

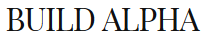

There exist two most common techniques for constructing multifactor portfolios. The mixing approach creates single-factor portfolios and then invests proportionally in each to build a multifactor portfolio. The integrated approach combines single-factor signals into a multifactor signal and then constructs a multifactor portfolio based on that multifactor signal. Which methodology is better? It is hard to tell, and numerous papers show each method’s pros and cons. The recent paper from Joris Blonk and Philip Messow explores this question from the standpoint of the credit fixed-income portfolio manager and offers their analysis, which shows that an integrated approach is probably better in this particular asset class.

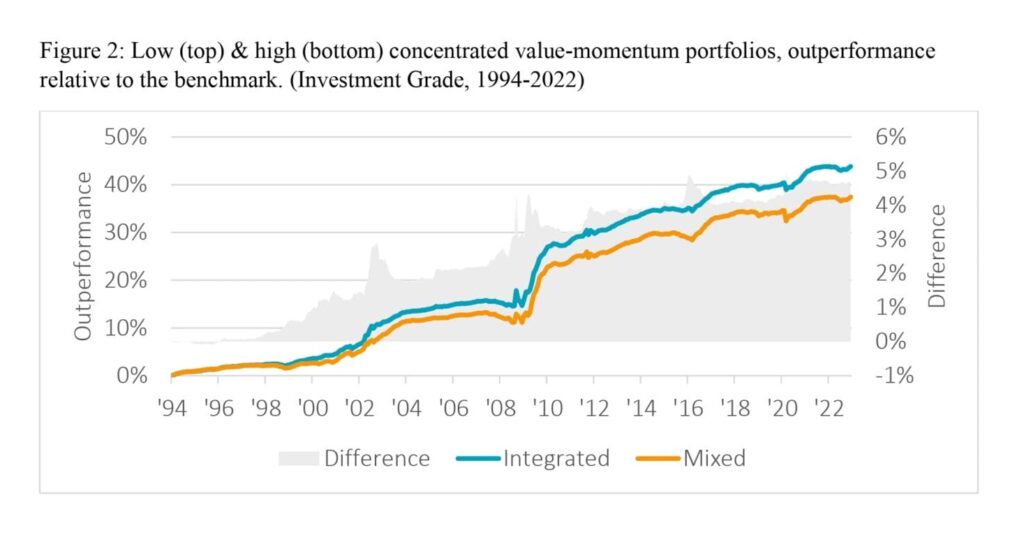

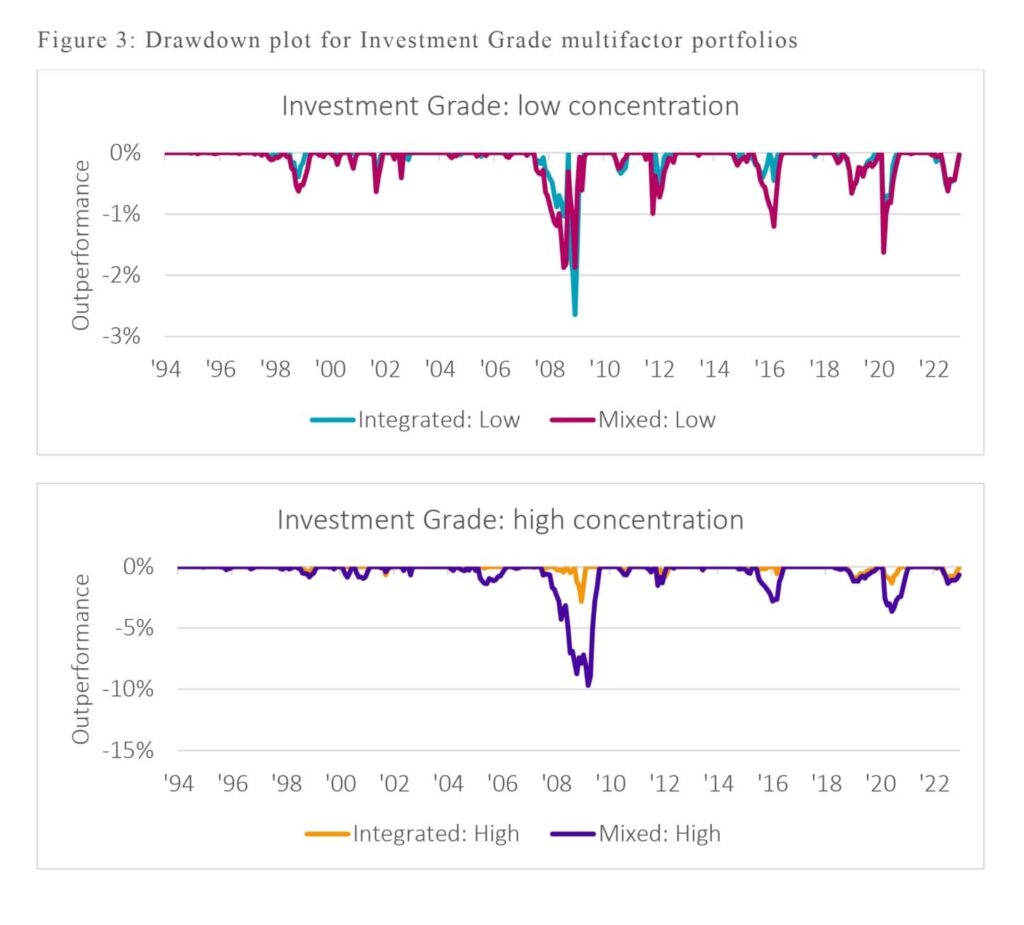

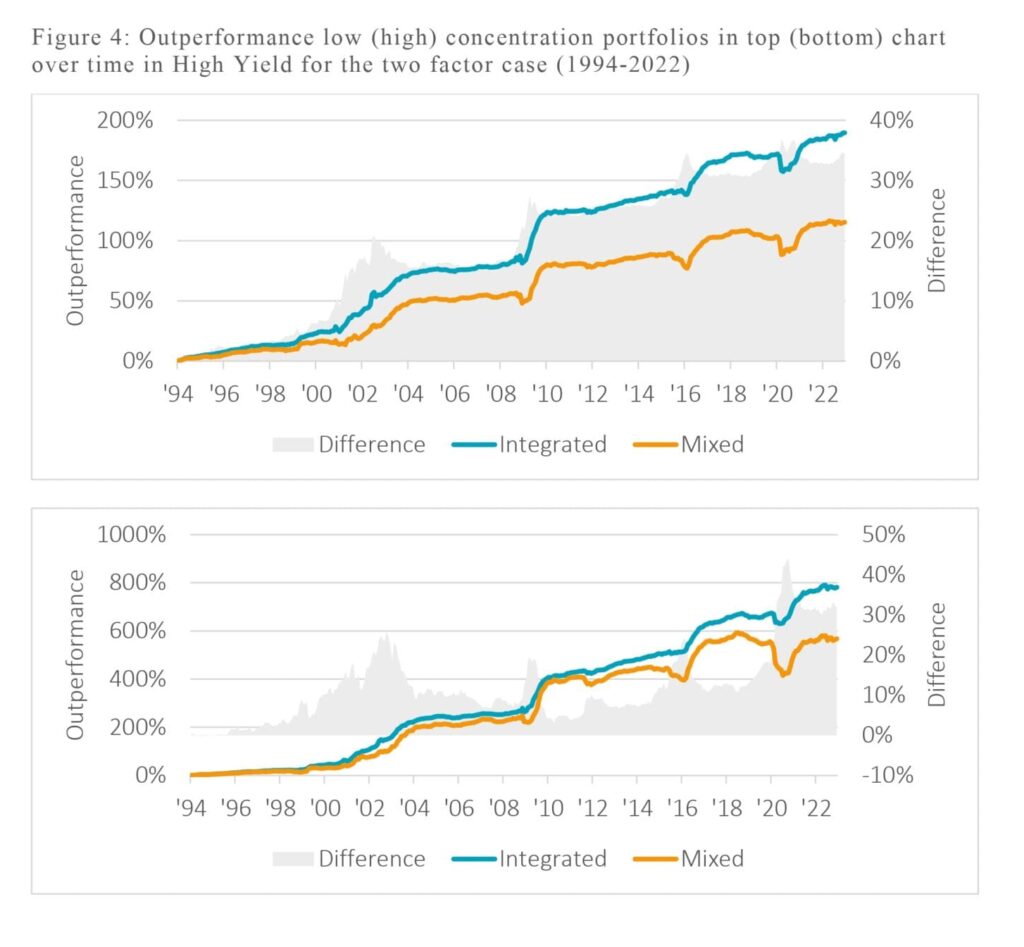

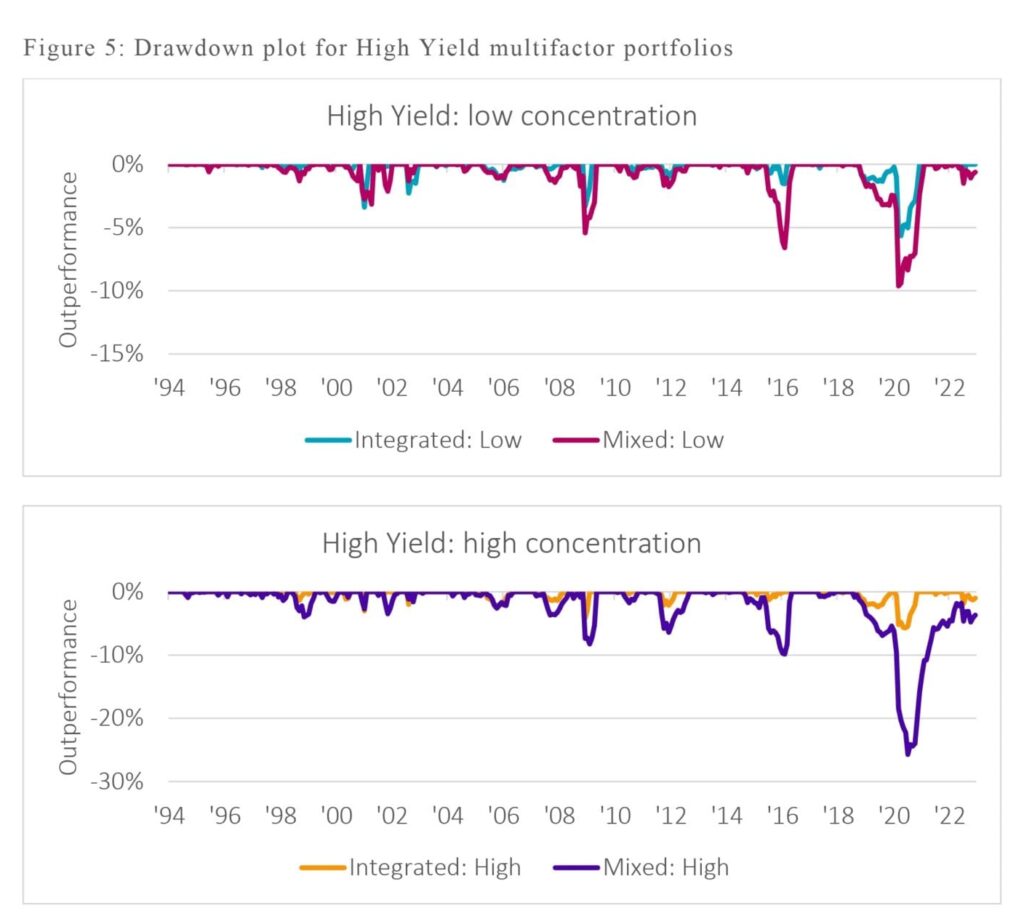

To make these two approaches comparable, authors use exposure-matched portfolios and limit themselves to long-only portfolios, as long-short strategies are more of a theoretical construct than a realistic, practical application for corporate bond investors. The authors found consistent results that indicated that integrated multifactor portfolios outperformed mixed multifactor portfolios. These results hold across different investment universes (Investment Grade and High Yield), different underlying factor suites (two or four factors), different exposure concentrations (low or high), and different market environments (falling/rising interest rates, falling/rising credit spreads, etc.).

In addition, they show that an integrated approach reduces downside risk by avoiding investing in bonds with offsetting single-factor exposures (e.g., high value & low momentum), the so-called “value traps.” Most studies in the credit factor investing literature lack an answer to implementing these strategies under realistic conditions and achieving attractive risk-adjusted returns. Their analysis provides a first direction for translating these theoretical studies into “real” portfolios. Therefore, this study has important implications for practitioners who want to implement multifactor strategies for corporate bonds.

The next logical step would be to ask another question – which approach is better in all-equity investment universe where shorting is allowed and easier?

Authors: Joris Blonk and Philip Messow

Title: How to Construct a Long-Only Multifactor Credit Portfolio?

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4775767

Abstract:

This paper examines how to combine single factors into a multifactor portfolio of corporate bonds. The two most common approaches in the literature are the so-called ‘integrated’ and ‘mixing’ approaches. This paper analyzes these two methods in corporate bond markets, and finds that the integrated factor portfolios generally lead to higher risk-adjusted returns. This is largely due to the fact that they do not invest in underperforming bonds that score poorly on a single factor, to which the ‘mixing’ approach is exposed to. Our results are robust over time and hold in different macro environments and in both Investment Grade and High Yield markets.

As always, we present several exciting figures and tables:

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

“

“Mixing” requires two steps. The first step is to create portfolios based on the individual factors, and then to create a mixed portfolio from these individual portfolios by investing proportionately in each of the individual factor portfolios.

The “integrated” approach requires the construction of only a single portfolio, as the individual signals are first combined into an overall signal and the portfolio is then constructed on the basis of this multifactor signal.

The debate in the academic literature has focused primarily on the question of which approach provides higher risk-adjusted returns. Proponents of integrated multifactor portfolios argue that this approach avoids securities with opposite factor loadings (i.e., securities that perform well on one factor but poorly on another) while favoring securities with balanced positive exposures to the desired factors. This tends to reduce turnover and thus transaction costs, which are particularly important in the credit space.

However, there are also arguments for mixing. In equities, for example, studies show that there is little difference in performance between methods in areas of low tracking error. Mixing does, however, facilitate performance attribution, as the over- or underperformance of the multifactor portfolio can be directly attributed to the underlying individual factor portfolios. This increases the transparency of the investment approach. We examine which of the two approaches, integrated or mixing, is more useful in the corporate bond market. There are some unique features of the bond market, such as the separation between Investment Grade and High Yield, or the higher implementation costs of active strategies, which may lead to different results than on the equity side. We focus on the practical application of long-only credit portfolios, as shorting corporate bonds is particularly challenging because shorting costs are even higher compared to equities.”

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Sign up for our newsletter or visit our Blog or Screener.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Premium service? Check how Quantpedia works, our mission and Premium pricing offer.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Pro service? Check its description, watch videos, review reporting capabilities and visit our pricing offer.

Are you looking for historical data or backtesting platforms? Check our list of Algo Trading Discounts.

Would you like free access to our services? Then, open an account with Lightspeed and enjoy one year of Quantpedia Premium at no cost.

Or follow us on:

Facebook Group, Facebook Page, Twitter, Linkedin, Medium or Youtube

Share onLinkedInTwitterFacebookRefer to a friend