The Hidden Costs of Corporate Bond ETFs

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) have been recently booming in popularity and enjoy great praise for their flexibility and accessibility in terms of liquidity. They allow investors convenient exposure to less liquid assets such as corporate bonds. But liquid ETF instrument based on illiquid assets is a recipe for a lot of hidden problems (and sometimes disasters), especially in such a turbulent period on fixed income markets as it’s now.

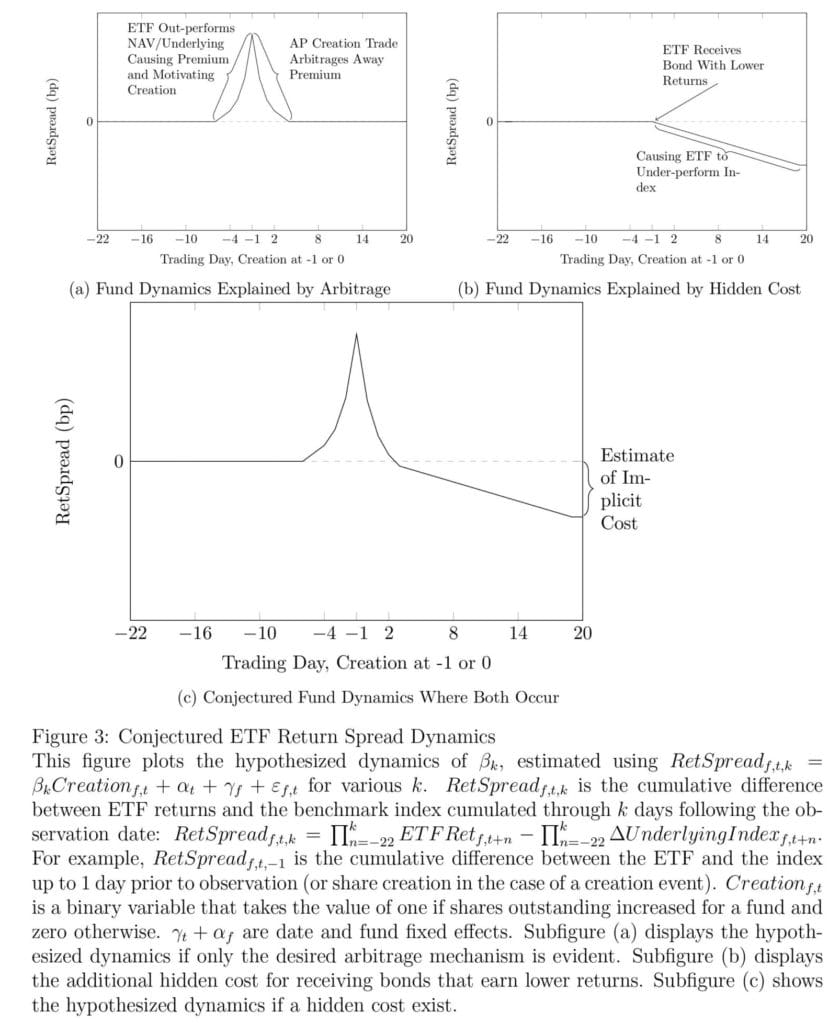

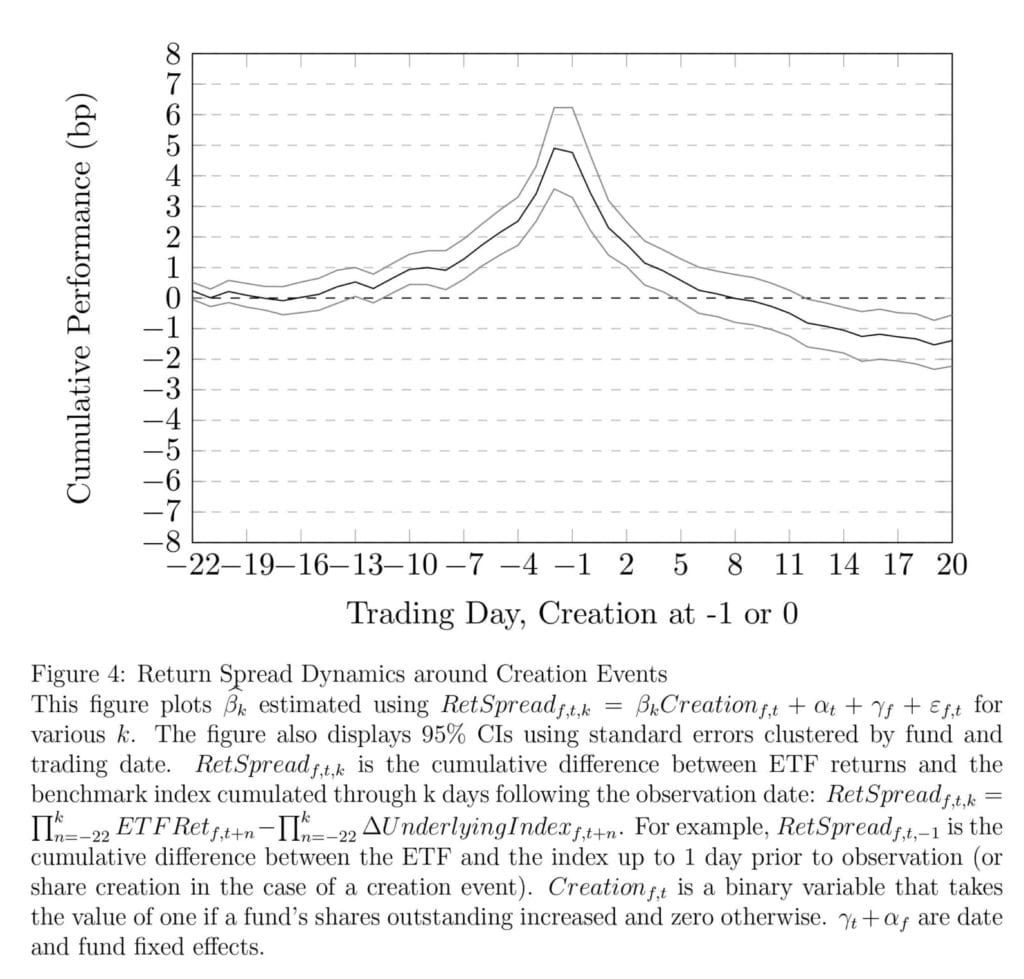

There are various certain specifics which come with creation of new ETFs and problems for buying of underling prospects to match the fund’s NAV. Chris Reilly’s paper (2022) revolves around the point that ETF managers encourage Authorized Participants (APs) to more aggressively arbitrage tracking errors to the benefit of ETF investors while simultaneously allowing APs to interact strategically with ETF portfolios at the expense of ETF investors. The author found that delivered bonds do not underperform because ETFs hold low-risk or high-liquidity subsets of underlying benchmarks and receive lower compensation for their lower risk. But instead, ETF holdings shift in the time series, and ETFs increase holdings in bonds when the short-term future return on those bonds. But why is that?

Consistent with APs learning from the order flow of their informed customers, dealer inventories increase in the 5 days before a bond is delivered into an ETF portfolio. On the day a bond is delivered to ETF portfolios, dealer inventories instead fall, consistent with APs simultaneously seeking to reduce their inventories through their market-making activities and via ETF share creations. It is taken that ETF investors are aware of the hidden cost, and the magnitude of the cost reveals a high willingness to pay for the liquidity transformation provided by corporate bond ETFs despite the hidden cost being high.

Underlying asset liquidity is a first-order determinant of optimal security design for ETFs. While these ETFs do underperform their benchmark by greater than their stated net expense ratios (as much as claimed 48 bps p.a.), they still offer a liquid alternative for investors that do not have the resources to manage their own fixed income portfolio. This summary could be taken as a good reminder that investors’ expenses to obtain liquidity in the fixed income space are often quite substantial.

Author: Christopher Reilly

Title: The Hidden Cost of Corporate Bond ETFs

Link: https://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=4147882

Abstract:

I document a hidden but substantial cost associated with the liquidity transformation that corporate bond exchange-traded funds (ETFs) provide. When creating new shares, authorized participants (APs) deliver a subset of the portfolio of bonds that underlie a corporate bond ETF. This subset contains bonds that realize low future returns, reducing ETF performance by 48 basis points per annum. This loss in performance cannot be attributed to forgone compensation for risk or illiquidity, but instead results from APs utilizing information regarding future changes in bond values to strategically deliver bonds when those bonds are expected to realize poor performance in the near future.

As always we present several interesting figures:

Notable quotations from the academic research paper:

“To provide a number of advantages, such as intraday liquidity, ETFs are designed to be traded on secondary markets. Insofar as ETFs will have secondary-market prices that do not necessarily equal the value of their underlying assets and because the vast majority of investors will purchase ETFs via this secondary market, ETFs require a mechanism that enables them to remove large discounts or premiums that differentiate net asset values from ETF share prices.5 To facilitate the elimination of discounts and premiums, ETFs enter agreements with APs, who are allowed to create and redeem ETF shares by exchanging the assets that underlie an ETF share for a share of the ETF or vice versa. This process is referred to as “in-kind exchange.” Consider a highly stylized and simplified example: suppose investors wish to hold an ETF that tracks the S&P 500 and purchase a sufficiently large quantity of the SPY ETF to positively impact SPY’s secondary market price. This creates a premium in which the ETF trades at a higher price than the underlying assets. APs can seek to arbitrage this premium away by buying the underlying assets and selling short shares of the ETF. An AP notifies an ETF manager that it wishes to create a share as outlined in their agreement. At the end of the trading day, the AP delivers all of the underlying assets, receives newly created ETF shares and utilizes these shares to cover the short-sale position, thereby locking in the arbitrage profit. Because all relevant shares of the S&P 500 companies still underlie the SPY ETF, investors who hold the ETF throughout this entire process face no costs. Specifically, the ETF experiences a temporary tracking error induced by the premium but when the premium is arbitraged away the tracking error reverses and the buy-and-hold ETF investor receives a return that exactly tracks the performance of the S&P 500 gross of the ETF net expense ratio. Thus, when all underlying assets are exchanged in kind, ETF investors are not impacted by other investors’ entry.

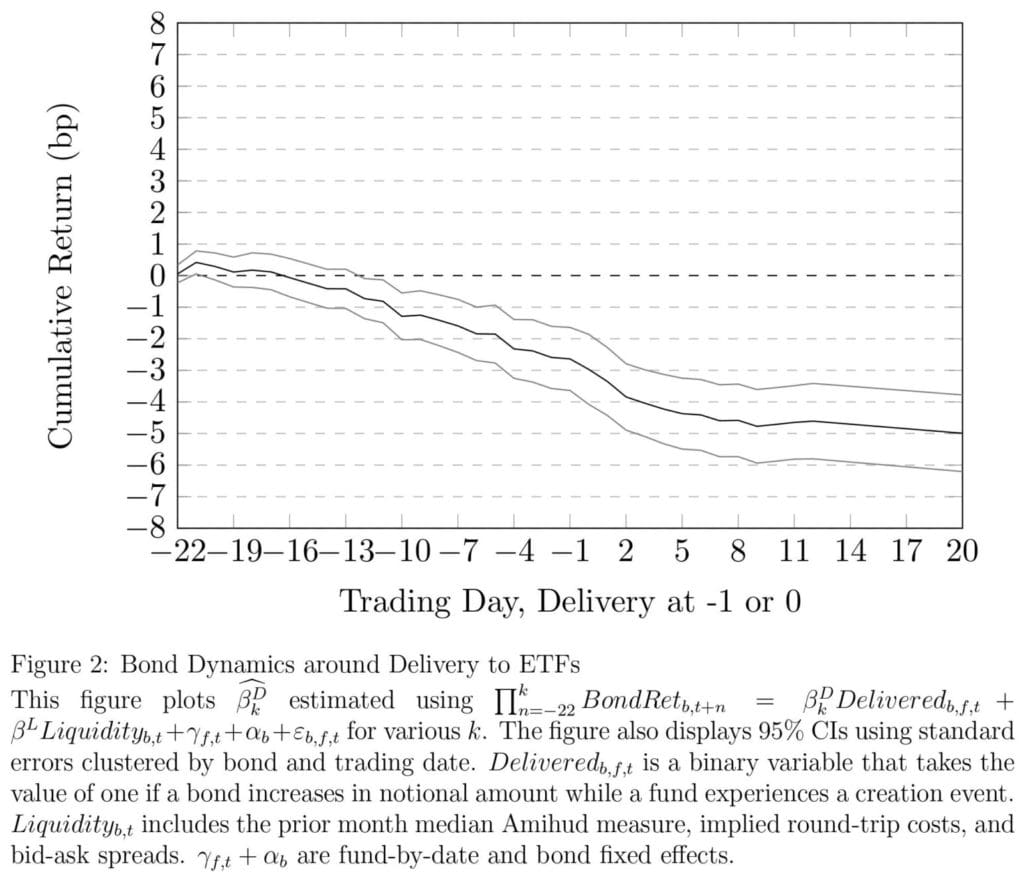

I estimate the effects of asset delivery on bond returns over horizons ranging from 1 to 42 trading days. Figure 2 displays the dynamics of the estimates of βkD across various k. The figure also shows 95 % confidence intervals using standard errors that account for two-way clusters by bond and by date. Full parameter estimates for select horizons can be found in Appendix Table A1. As can be seen, bonds that will be delivered begin underperforming in the month prior to delivery and the cumulative return is statistically significant by t=-12. By t=-1, the earliest date at which creation could occur,9 bonds that will be delivered have underperformed by 2.6 basis points. Thus, the pre-delivery performance is consistent with APs’ utilizing information when deciding which bonds to deliver and when. On net, it appears that APs rely on some combination of bond momentum and private information. Following t-1, bonds underperform by an additional 2.4 basis points in the following month. Thus, following receipt by ETFs, precisely when the ETF portfolio weights of these bonds increase, the bonds underperform going forward. This underperformance is evidence that ETFs receive an adversely selected set of bonds from APs that will hurt ETF performance relative to their underlying benchmarks. Importantly, this is identified with time-series shifts in portfolio weights, not persistent differences in ETFs’ portfolios and benchmark indices’ portfolios, and thus represents a pure performance drag.10 Thus, put simply, when ETFs experience creation events they receive inferior assets (assets with low expected future returns) from APs.

The return dynamics of delivered bonds both prior and subsequent to delivery are consistent with APs’ utilizing information regarding future changes in bond values to decide strategically which assets to deliver into ETF portfolios. Such strategic interactions provide marginal incentives on top of APs’ well-understood incentives to profitably arbitrage differences in ETF prices and underlying assets’ value. Theory clearly predicts when strategic behavior should be more profitable,and thus more likely to occur, conditional on observing a creation event, and finally therefore where the hidden cost should be the highest.

First, APs’ strategic incentives will be stronger when their information regarding future bond values is more valuable. It is well understood that agents are likely to possess more valuable information in less liquid or less efficient markets (in fact, agents who possess valuable information can endogenously make those markets less liquid in many classical market-microstructure models). Additionally, ETF managers adopt less stringent share- creation rules in the presence of asset liquidity. Therefore, the hidden cost should be higher when underlying assets are less liquid.

Second, APs’ ability to deliver bonds strategically is enhanced when they are required to deliver fewer bonds. If an AP has information that is relevant to the future performance of a given bond that will impact their expected profits from a creation trade, the impact will be much greater if that bond is one of ten bonds that needs to be delivered versus being one of a hundred bonds to be delivered. Moreover, it may be easier for APs to acquire information about the idiosyncratic performance of a small number of bonds. Thus, when creation baskets are large, it is more difficult for APs to acquire information regarding the average performance of a given creation basket and the strategic incentive will be relatively

weaker, enabling the arbitrage incentive to dominate.

APs need not possess superior bond picking skills nor act unscrupulously in order to deliver bonds with lower performance in a manner than embeds the hidden cost. APs may simply deliver the bonds that they can acquire easily because other informed investors wish to sell it to them. Nonetheless, since informed customer order flow is not fully incorporated into bond prices used to settle creations, ETF investors may still face the hidden cost in exchange for the valuable liquidity transformation services that APs in conjunction with the ETF security design delivers.

The existence of the hidden cost I have documented implies that investors, either knowingly or unknowingly, pay a high cost for the liquidity transformation that corporate bond ETFs provide. Specifically, the cost results from modifications to creation rules that are designed to induce APs to conduct arbitrage trades despite the illiquidity of underlying assets. Many policymakers and academic researchers have expressed concerns over the fragility that might result from liquidity transformation. I demonstrate that, even if asset illiquidity poses no risk to financial stability, liquidity transformation is not a “free lunch.” The concessions that ETF managers must make to induce arbitrage activity incur a high cost as a result of APs’ ability to interact strategically with the rules. Because this cost results directly from asset illiquidity, the framework of Chordia (1996), which implies that the more illiquid the underlying assets are, the higher are the barriers to investor fund flows, likely extends from mutual funds to ETFs. This cost of liquidity transformation also helps to rationalize flow performance relationships in ETFs and to resolve open puzzles in the important strand of literature that examines flows to investment managers. Last, as the cost of such liquidity transformation is higher than the explicit fees reported by corporate bond ETFs, the findings I have reported in this paper are of the first order in describing the performance realized by ETF investors.”

Are you looking for more strategies to read about? Sign up for our newsletter or visit our Blog or Screener.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Premium service? Check how Quantpedia works, our mission and Premium pricing offer.

Do you want to learn more about Quantpedia Pro service? Check its description, watch videos, review reporting capabilities and visit our pricing offer.

Are you looking for historical data or backtesting platforms? Check our list of Algo Trading Discounts.

Would you like free access to our services? Then, open an account with Lightspeed and enjoy one year of Quantpedia Premium at no cost.

Or follow us on:

Facebook Group, Facebook Page, Twitter, Linkedin, Medium or Youtube

Share onLinkedInTwitterFacebookRefer to a friend